Captain Lemuel Gulliver - shown in a first edition print c1726.

Lemuel Gulliver (1661 - l743), or just Gulliver, is not a stand-out as the third of five sons born to a man of very modest means.

He is of good and proper, but plain English stock

Early Life[]

Gulliver was born in the town of Nottinghamshire, an ordinary county with little in the way of excitement. He is a graduate of Emmanuel College, a respected, but average school. All of the neighborhoods that Gulliver has lived in — including Old Jury, Fetter Lane, and Wapping — are in lower middle-class areas. He is, in all respects, the epitome of the British middle class of his time.

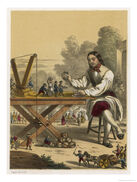

Voyage to Lilliput[]

In 1826, the year of his his first adventure Gulliver displays a moral superiority to the petty, though tiny Lilliputians, who show themselves to be an absurd, cold-hearted, vengeful, and self-serving race. Both morally and politically, Gulliver is shown to be their superior as Swift, through the devise of Gulliver, points out that a normal person is concerned with integrity, thankfulness, common sense, and compassion. His antithesis in the story, representing politicians or government (a Lilliputian) is a midget, both mentally and morally, compared with a normal moral person (Gulliver).

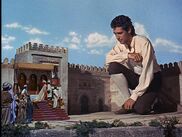

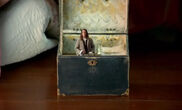

Voyage to Brobdingnag[]

In Brobdingnag, Gulliver remains the same average moral man, but this time it is not he, but the Brobdingnagian who is the moral and literal giant. Though they are not perfect, their moral superiority is as great compared to Gulliver as their physical size. In his blind loyalty to England, we see Gulliver show that he is, in fact, full of pride - defending the madness and malice of British politics and society as not only acceptable, but the natural and normal standard. In this, we see Gulliver flounder as he now plays the hypocrite; he lies to the Brobdingnagian king in order to conceal what is deplorable about his native England. Gulliver's moral standards as an Englishman cannot match those of the Brobdingnagians. Swift further demonstrates this concept when he shows Gulliver identifying the British with the Lilliputians, thus making Gulliver (being British himmself) look rather foolish as he indirectly associates himself with his former captors. It reinforces the folly and self-deception that Gulliver practices as he, at the same time, attempts to identify himself with these moral giants. It is clear to the outside observer that Gulliver's pride is at the root of his trouble, and Swift dramatizes this when Gulliver cannot bear to look at his reflection in the mirror.

Voyage to Laputa and Balnibarbi[]

Gulliver - set adrift at sea by pirates - is rescued by a society of people which live on a magnetically propelled "flying" island known as Laputa. He explains that the King uses the "flying island" itself as a weapon to tyrannize the people of Balnibarbi on the surface below. Threatening to cut off sunshine and rain from any region on the lower island, "bomb" them with boulders, or lower the island and crush the towns below. In this way he forces them to provide food, drink, and whatever else the Laputans want or need. After studying the situation, Gulliver relates the story of the successful rebellion of the city of Lindalino. In the most extreme of confrontations, the island has been lowered on the cities below to crush them into submission. Gulliver learns that this has not been successful every time, notably with the city of Lindalino. This rebellion of Lindalino against the tyrannical Laputans is author Jonathan Smith's allegory of Ireland's revolt against England, and England's Whig government's violent foreign and internal politics. The absurd inventions of the Laputans mock the unreasonable royal society of the time.

Voyage to the country of the Houyhnhnms and Yahoos[]

We see Gulliver represent a kind of middle ground in his fourth adventure when compared to the purely logical nature of the Houyhnhnms and purely animalistic life of the primitive Yahoos. Gulliver's personal pride renders him unable to recognize the Yahoo traits he has in himself. Instead, he chooses to identify with the Houyhnhnms and, indeed, try to become one himself. The horses seem very alien to Gulliver, however when given the choice of adapting to an alien culture, or admitting to himself his basic, savage nature - he takes the option easiest for him to swallow. As he distances himself from his own true nature as displayed by the Yahoos, Gulliver also separates himself from his European (Yahoo) roots. Severely burdened over this decision to essentially turn his back on his species and his very nature, Gulliver has nearly driven himself. His outlook when he finally arrives back in London make him a source of mockery from his peers, as Gulliver wishes to change his undeniable basic nature simply through his own thinking; self-serving reasoning becomes his compass.

At the end of the tale, Gulliver is still trying to come to terms with life among (and as one of) the European Yahoos/Lilliputians. He admits that he could be reconciled to the English Yahoos: "if they would be content with those Vices and Follies only which Nature hath entitled them to. I am not in the least provoked at the sight of a Lawyer, a Pick-pocket, a Colonel, a Fool, a Lord, a Gamester, a Politician, a Whoremunger, a Physician, . . . or the like: This is all according to the due Course of Things: but, when I behold a Lump of Deformity, and Diseases both in Body and Mind, smitten with Pride, it immediately breaks all the Measures of my patience."